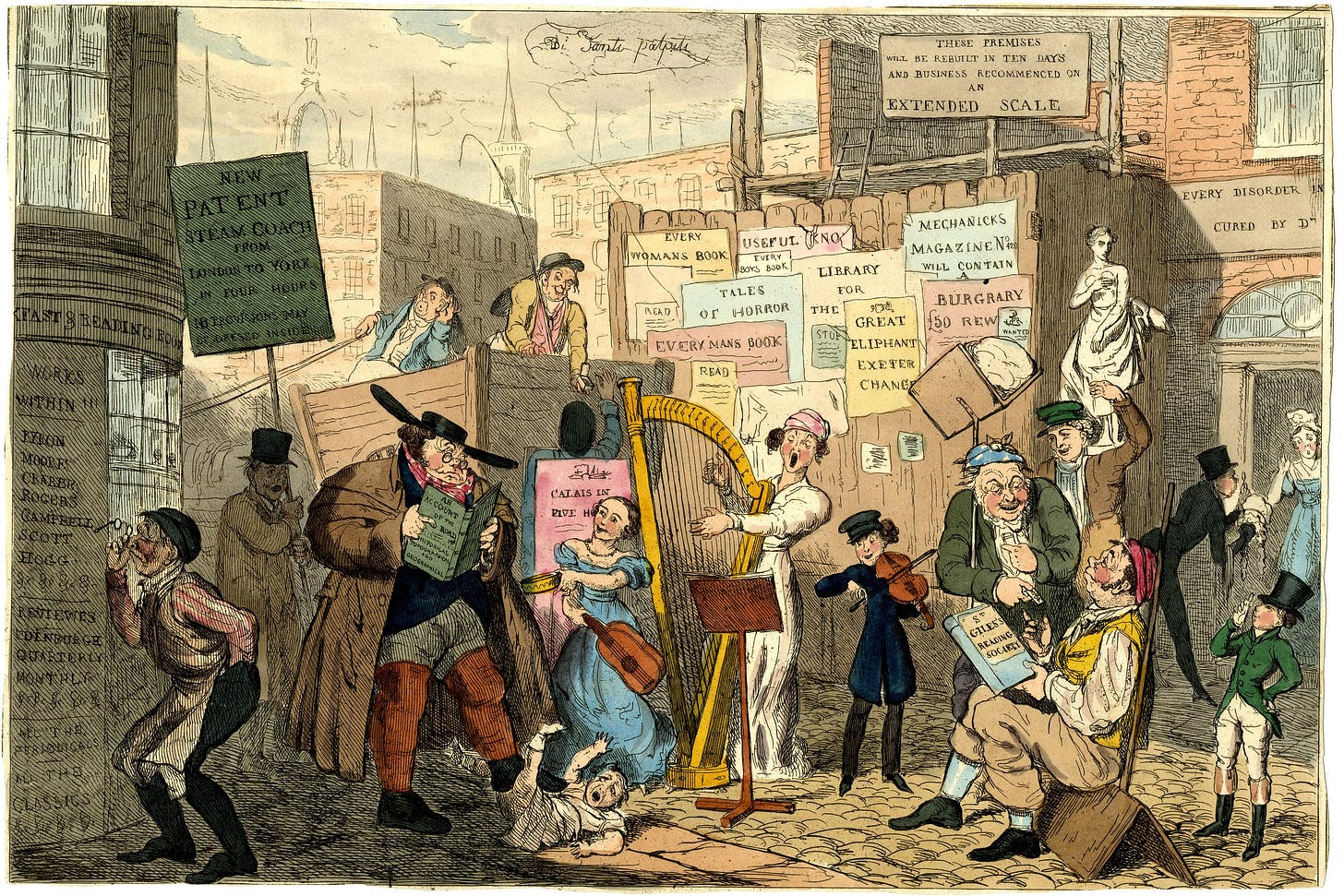

Reading was a touchy issue back in the 18th century. By this time, the sum of the printing revolution started by Gutenberg, Luther's bold proposal of translating the Bible into vernacular languages, and the Enlightenment's push for universal literacy, started to yield widespread results1.

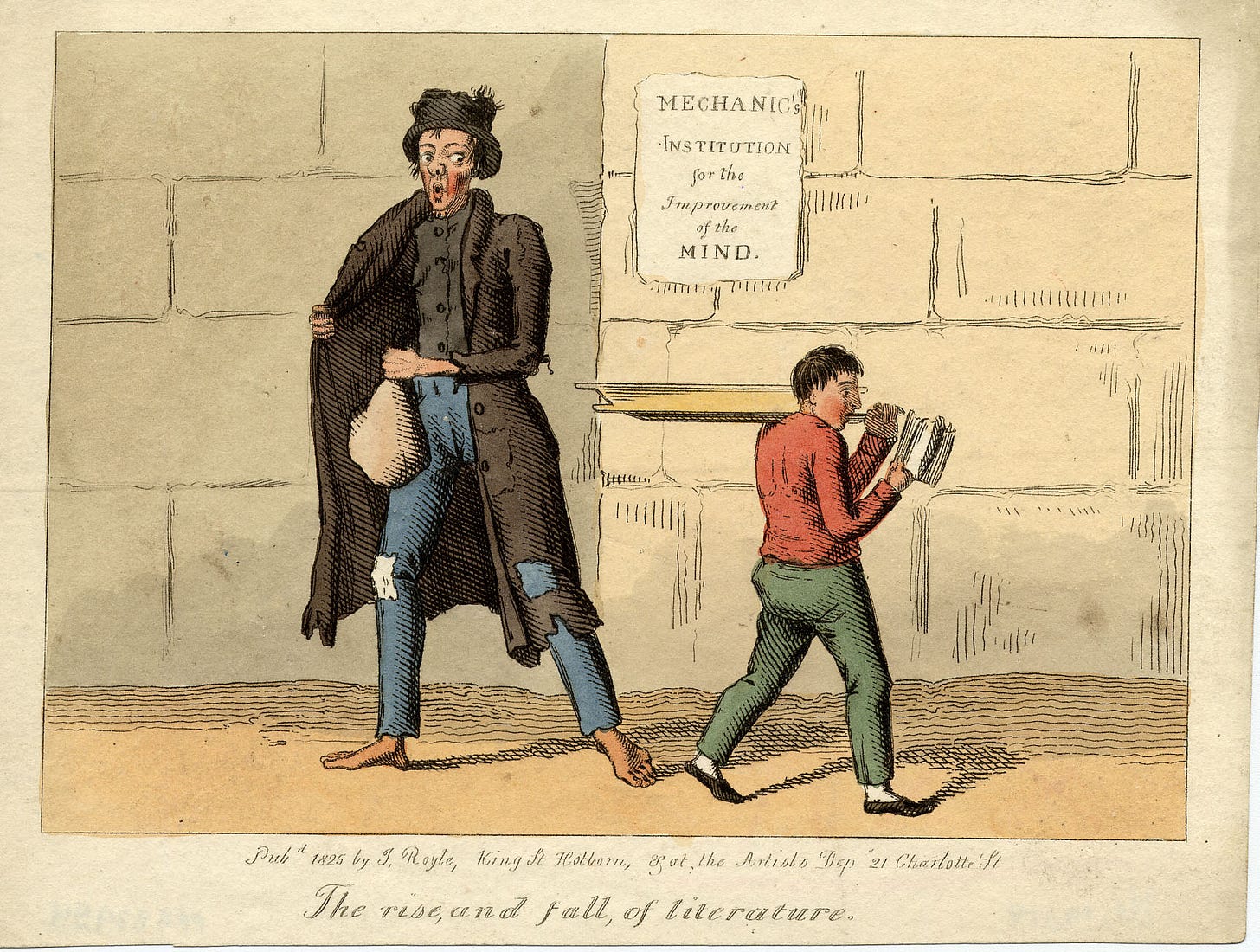

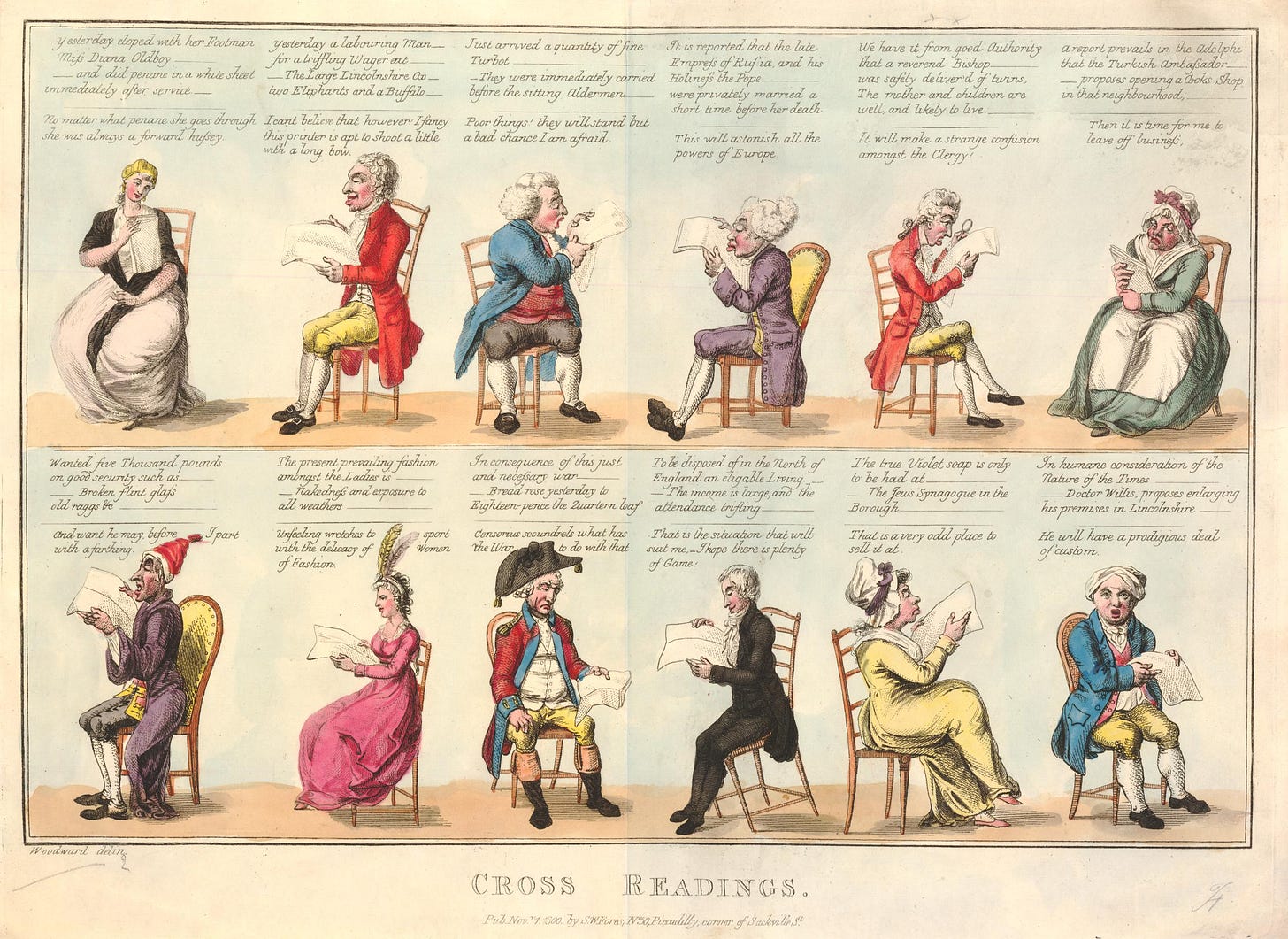

For the very first time, the number of literate females was not statistically irrelevant. At least in the western industrialized world, a lettered woman was no longer a circus-worthy anomaly, as in the times of Sappho or Christine de Pizan. Educated workers and lower-class folks were also increasingly common, and they were walking around in broad daylight, carrying books and newspapers under their arms as if it were no big deal.

But it actually was. There was a sense of unease in the air: a feeling that there were too many people reading, too much reading being done, too many texts being read in too many ways, for too many purposes and reasons. As access to and consumption of texts underwent drastic changes, reading became much more solitary than it had ever been before. It grew far more discreet, sneaky, easy to access, hide, and conceal.

Some thought that certain ilks of people shouldn't even have access to literacy. Others believed that literacy itself was either a positive or at least a neutral tool, but worried about what these new readers would read, when, how, where, how much they would read, and at whose expense2.

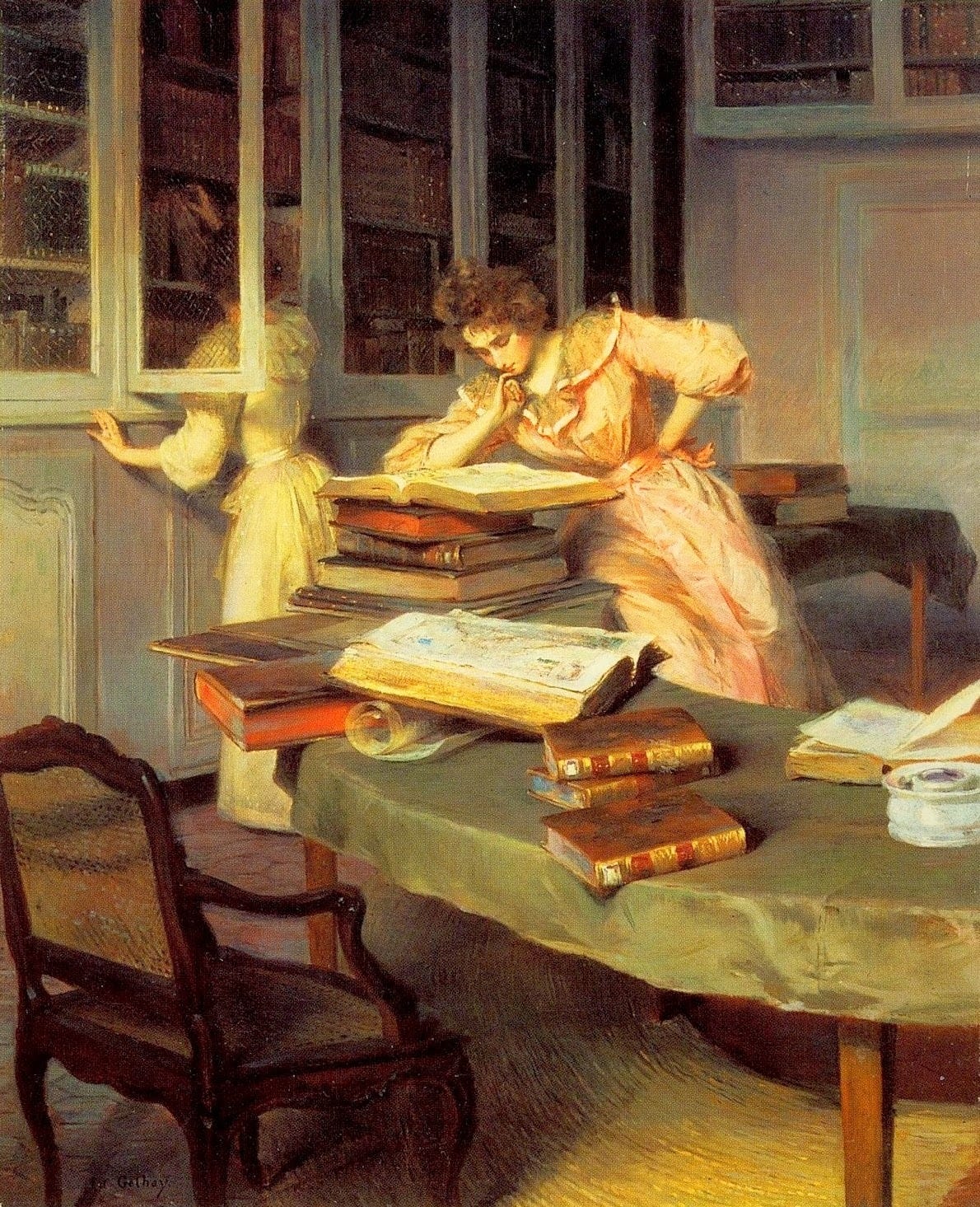

They wondered what they would glean from their readings and what kind of relationship they would establish with the texts. Would they conflate truth and fiction? Would the absorption spawned by reading make them antisocial or oblivious to their duties? Would they have their heads turned by books? Would they grow clumsily ambitious, now that they caught a glimpse of things far beyond their circumscribed lives? Most likely, yes.

Privacy was a danger and was also endangered. In the late 6th century, Augustine was taken aback when noticed that Ambrose preferred to read silently: his lips motionless as his eyes and mind devoured the pages. In fact, reading aloud, even in solitude, was the norm until at least the 17th century. Suddenly, everything changed, and almost everyone was reading in perfect quietness3.

That was cute, except when it wasn't. Take letters, for instance; people were crazy about exchanging them. But then, your wife would be sitting beside you, reading a letter whose contents you were unaware of. Think of the insecurity many of us feel about flirtatious partners texting other people in the middle of a family dinner. Now imagine that in a way more controlling and sexist society4.

You might have thought that your daughter was safe at home, shielded from the pernicious influences outside your respectable roof, while her mind was soaking up all kinds of filth made available by novels and letters written by who knows whom. Consider what happened to poor Cécile Volanges in Dangerous Liaisons5.

She was only fifteen, for God's sake. And it was all so settled. Madame Volanges was so zealous about her daughter's respectability that she only took her out of the convent a few months before the girl's wedding to the Comte de Gercourt. Cécile hardly left the house, and the only man she interacted with on any regular basis was her naive, well-meaning music teacher — our beloved Chevalier Danceny. Even so, all classes took place at home, where Madame Volanges could easily keep an eye on the young people.

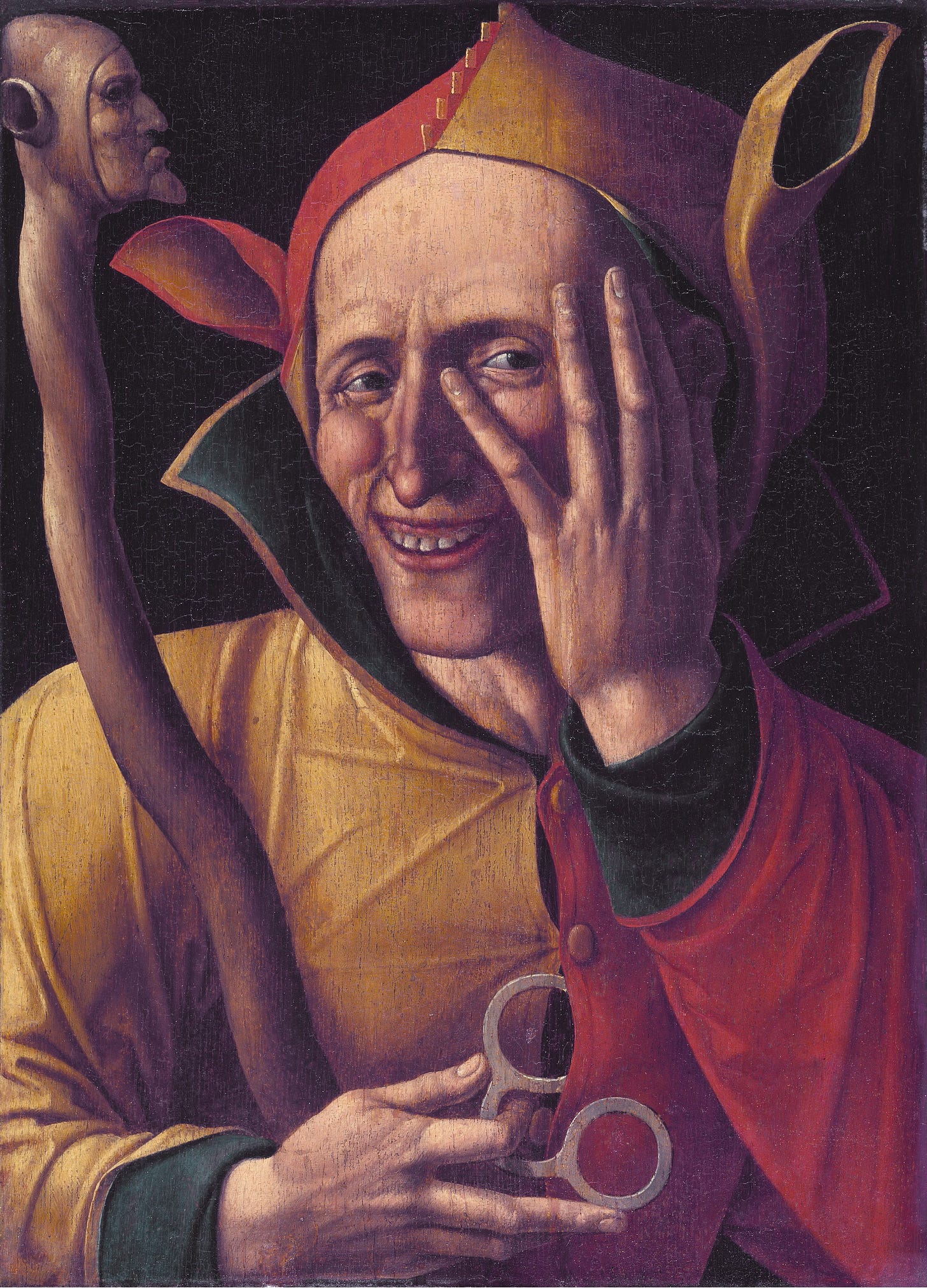

Still, there was no convent wall or maternal diligence to match the nasty influence of the Marquise de Merteuil. Peerless in the sordid art of letter writing, she cast her sinful web over the lives of both Cécile and Danceny, bringing down the honorable Présidente de Tourvel and even the savvy Vicomte de Valmont as collateral damage. By the end of the novel, the body count was impressive. All this for what exactly? Just to get back at Gercourt, who had the audacity to turn her down for somebody else.

There is something innate in Merteuil's villainy, that's for sure. But where did she manage to polish her congenital amorality? Where did she learn how to turn her own bad thoughts into other people's bad reality? She learned from the novels, of course. Not just from second rank romans libertins, but also from Rousseau — her favorite. The same novels that Madame de Staël saw as the great civilizers of modernity could be weaponized both in the hands of unwary, incompetent readers like Emma Bovary6, and in the hands of overly competent readers like Merteuil.

The situation was so bleak that even our good, traditional readers — i.e., straight, white men from western, industrialized, upper classes — had suddenly forgotten how to read properly7. They were becoming feminized and overly sensitive, letting themselves be emasculated by third-rate literature that was either aimed at women or, even worse!, written by women8.

We were leaving a world dominated by intensive reading made mostly by experts who would wade through the same few books gazillions of times, insistently reflecting, and discussing each passage, to a world of extensive reading in which all sorts of people would cast their eyes over an unprecedented amount of written materials on a daily basis, taking little to no time to reflect on the meaning of any specific piece.

So, yes, most of the 18th century concerns about reading came from conservative elites whose power and prestige were shaken by the loss of their monopoly over written materials. However, not all of their arguments were devoid of sense, nor were they defended only in cynical terms by people who did not believe what they said.

Take the Catholic Church, for instance. One of the reasons it opposed the idea of laypeople reading the Bible was the fear that it would surely lead to misinterpretations. This argument does not strike me as far-fetched even today.

Moreover, anxieties about literacy were not just an 18th century fad. In his 370 BC dialogue, The Phaedrus, Plato reported Socrates' distrust of writing in a similar vein. He felt that writing was a reckless scheme that created an unnatural split between the writer and his ideas.

Face-to-face interaction would be unbeatable since it allows one to tailor their exposition according to the characteristics of their specific interlocutor and gauge the audience's reaction in real-time, adjusting arguments as they speak. In contrast, writing would disempower the arguer in every possible way, leaving no room to explain oneself better, calibrate, modulate, reason, or revamp one’s claims.

To think that whenever someone misunderstood his arguments that person would go around spreading misconceptions about his ideas drove Socrates crazy. He couldn't understand why readers would stare at zombie monologues, frozen in pieces of papyrus, instead of engaging in live dialogues with living proponents whom they could both influence and be influenced by, thus creating real knowledge.

— (...) There’s something odd about writing, Phaedrus, which makes it exactly like painting. The offspring of painting stands there as if alive, but if you ask them a question they maintain an aloof silence. It’s the same with written words: you might think they were speaking as if they had some intelligence, but if you want an explanation of any of the things they’re saying and you ask them about it, they just go on and on forever giving the same single piece of information. Once any account has been written down, you find it all over the place, hobnobbing with completely inappropriate people no less than with those who understand it, and completely failing to know who it should and shouldn’t talk to. And faced with rudeness and unfair abuse it always needs its father to come to its assistance, since it is incapable of defending or helping itself.9

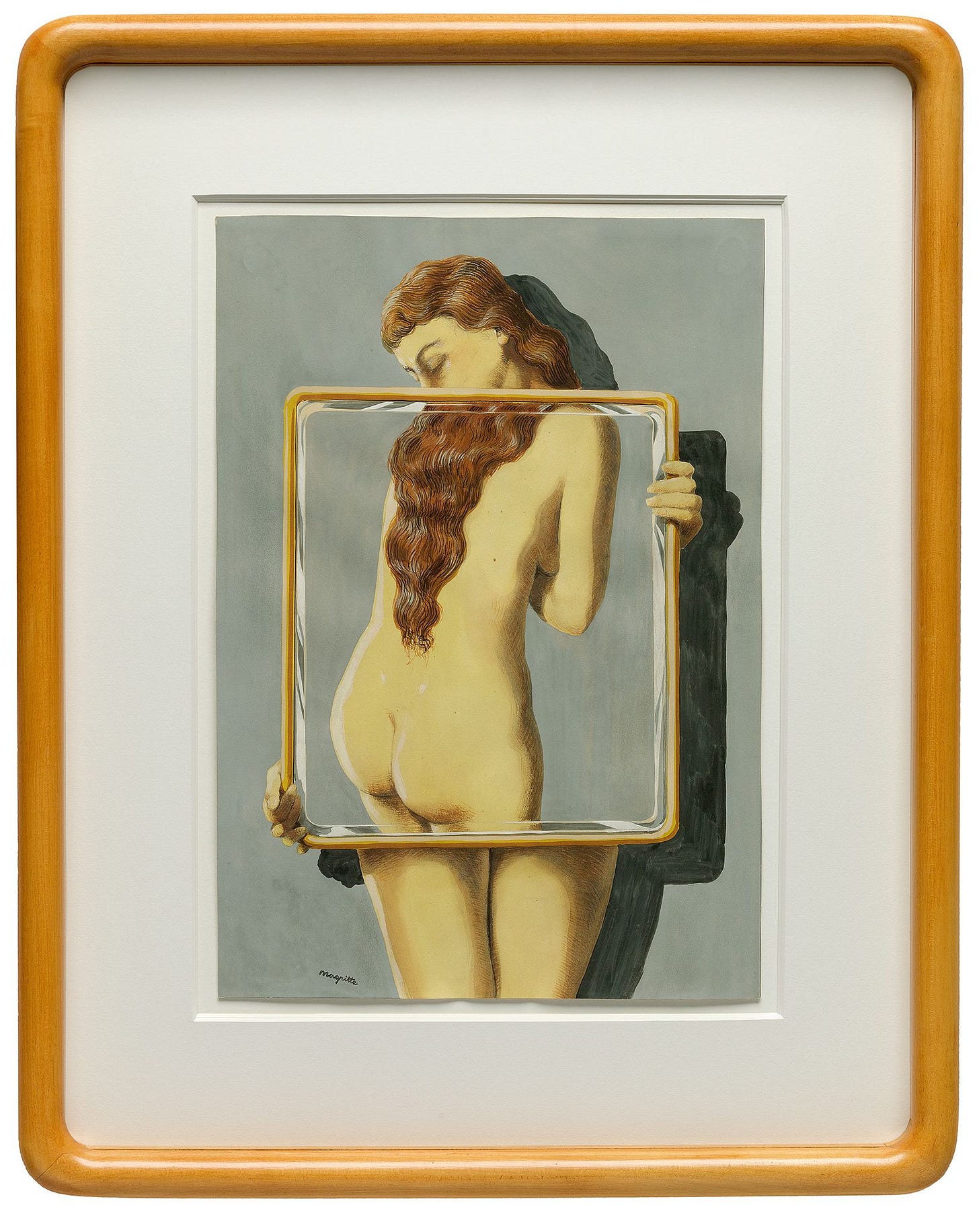

(I love how this quote unveils a kind of Mean Girls side of his argument. Amidst the countless drawbacks of written text, lies its impotence to choose who it will sit with at high school lunch. This image of ideas as helpless children is also a gem.)

The temperance side of the reading controversy also had its early debut, as the Roman stoic philosopher Seneca cautioned against intellectual gluttony in 65 BC. He argued that quickly devouring large amounts of books by a range of different authors would only lead to confusion.

Instead, a slow reading approach, allowing yourself to thoroughly dissect an idea before moving to the next one, would yield much better results in the long run, even if you end up knowing fewer authors and walking through fewer texts than your greedier counterparts.

Be careful lest this reading of many authors and books of every sort may tend to make you discursive and unsteady. You must linger among a limited number of master-thinkers and digest their works [...] for food does no good and is not assimilated into the body if it leaves the stomach as soon as it is eaten, and nothing hinders a cure so much as frequent change of medicine. [...] Each day [...] after you have run over many thoughts, select one to be thoroughly digested that day.10

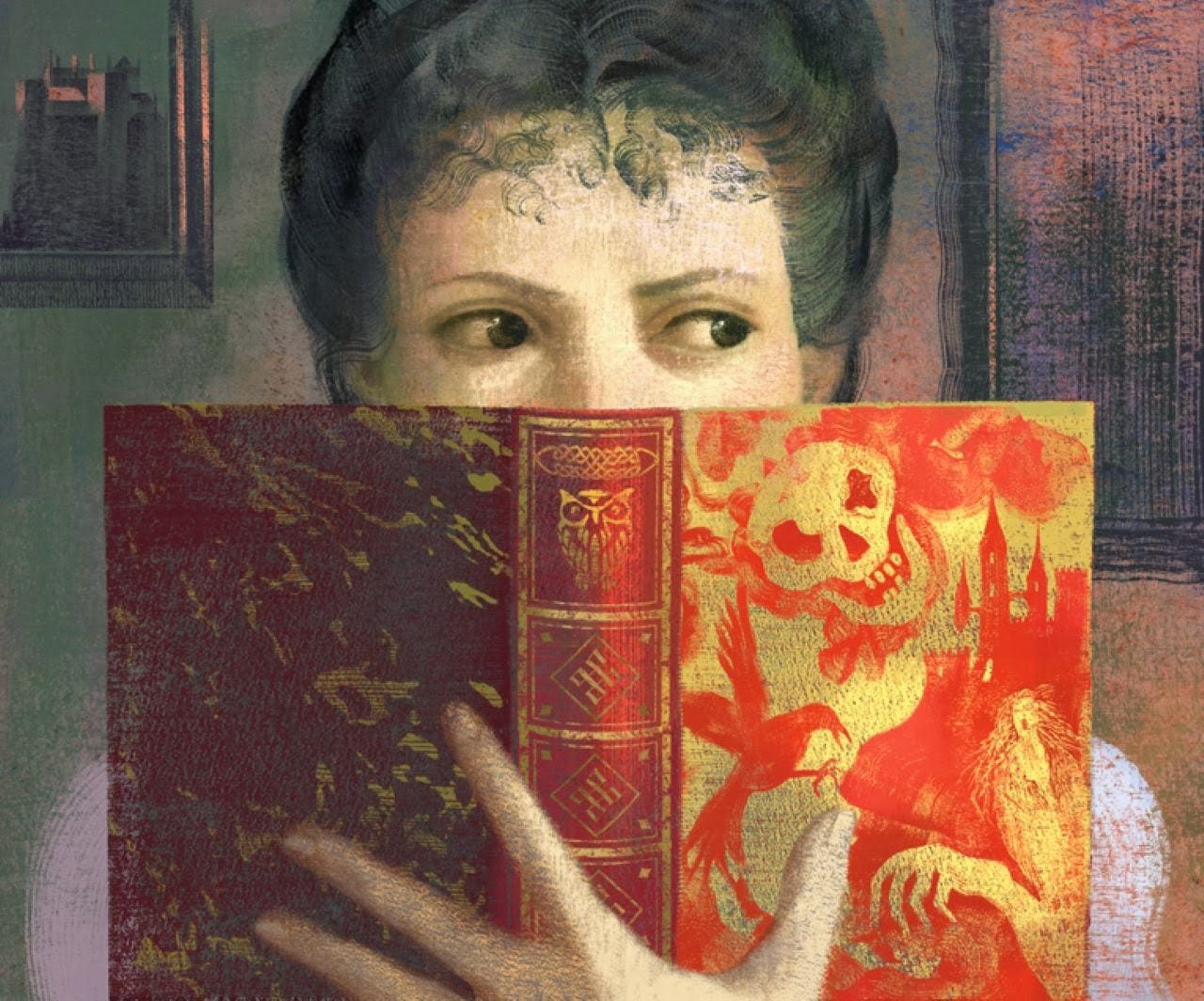

Contagious books, poisoned manuscripts, and textually transmissible diseases are also typical 18th century paranoias with a long prior history.

Perhaps this metaphor first appeared in “King Yunan and the Sage Duban”, a tale that is part of The Arabian Nights collection11. It tells the story of a wise man who manages to cure a leper king, receiving precious gifts, and a position as a royal advisor as a reward. These blessings, however, stir up the envy of the king's viziers, who convince the ruler that the poor sage was plotting to poison him12.

Unable to dissuade the monarch from the injustice he was about to commit, the sage decides that his death would at least be avenged. He gifts the king with a book that supposedly contains priceless wisdom, but makes sure to saturate every single page with a deadly poison. Thus, the ungrateful monarch dies, becoming a victim of the same intellect that had once saved his life.

Thanks for reading Já matei por menos — por Juliana Cunha! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

Throughout the Middle Ages, the Renaissance, and all the way into the Modern Age, poisoned books keep popping up in fiction works, in religious discourses against heretical texts, and in secular attacks against whatever was considered secularly heretical at that time.

Umberto Eco, for instance, was so fond of this image that he made it the motto of his first novel, The Name of the Rose13, set in the Middle Ages. In the book, a monk laces the pages of the missing second tome of Aristotle's Poetics that supposedly deals with comedy with arsenic.

Considering laughter to be somehow heretical but not daring to destroy the last available copy of such an important work, the monk decides to poison the manuscript, counting on anyone who ventured to read its pages to have to lick their fingers to turn them, and thus dying poisoned. This ingenious strategy creates a sort of victimless crime, as readers would only be poisoned to the exact extent of their undue curiosity.

So, I think it's pretty clear that people have had issues with reading basically since always. However, these concerns never reached the level of a massive wave of hysteria as they did from the late 17th century onwards, and it had everything to do with the rise of both mass literacy and the modern realist novel as the prevailing literary form.

(to be continued)

Literacy was a crucial ground of the dispute between the Catholic and Protestant churches. Promptly in the 16th century, literacy campaigns inspired by Luther were conducted in German states and Scotland. In the 17th century, it was Sweden's turn to initiate its first religious campaigns promoting reading and in the 18th century, France, Spain and England followed the same path. The Rise of Mass Literacy: Reading and Writing in Modern Europe, by David Vincent. Polity Press, 2000.

The Reading Lesson: The Threat of Mass Literacy in Nineteenth-Century British Fiction, by Patrick Brantlinger. Indiana University Press, 1998.

Space Between Words: The Origins of Silent Reading, by Paul Saenger. Stanford University Press, 1997.

I Hope I Don't Intrude: Privacy and its Dilemmas in Nineteenth-Century Britain, by David Vincent. Oxford University Press, 2015.

Dangerous Liaisons, by Choderlos de Laclos. Translated by Helen Constantine. Penguin, 2007. First published in 1782.

Madame Bovary, by Gustave Flaubert. Translated by Adam Thorpe. Penguin, 2021. First published in 1856.

Men of Feeling in Eighteenth-Century Literature: Touching Fiction, by Alex Wetmore. Palgrave Macmillan, 2013.

Victims of the Book: Reading and Masculinity in Fin-de-siècle France, by François Proulx. University of Toronto Press, 2019.

Phaedrus, by Plato. Translated by Robin Waterfield. Oxford University Press, 2002, p. 70. Written around 370 BC.

As quoted in The Art of Living: The Stoics on the Nature and Function of Philosophy, by John Sellars. Bloomsbury, 2009, p. 122. First published in 2003.

Papyrus: The Invention of Books in the Ancient World, by Irene Vallejo. Translated by Charlotte Whittle. Knopf, 2022. First published in 2019.

The Annotated Arabian Nights. Translated by Yasmine Seale, edited by Paulo Lemos Horta. Liveright, 2021.

The Name of the Rose, by Umberto Eco. Translated by William Weaver. Mariner Books, 2014. First published in 1980.